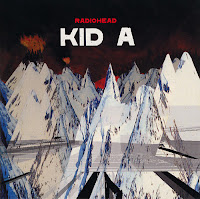

Radiohead

Kid A

(Parlophone 2000)

It’s been a decade since Kid A was unleashed but I’m caught between the desire to say something about it here, the danger of repeating what everyone else says about it, not wanting to add just another review to the legion of pieces written about Radiohead mark four, writing about something else that isn’t as populist that deserves more attention and that there’s the tendency inherent in any discourse on Kid A to make one sound like a pompous music snob, that something was got that everyone else didn’t, when there wasn’t really anything really difficult to get in the first place. All this weighs heavily on my psyche as I type, but there’s no escaping the fact that (and it’s difficult to admit publicly that there’s a singular like among the multiplicity of likes) Kid A is my favourite album.

Maybe it’s because Kid A is one of the few recordings that can be listened to in one sitting, as a unit, without any reflexes wanting to skip a track (1) or that the visual phenomenon of autumn is haunted by my first experiences with Kid A, that the three-year wait between OK Computer and Kid A was excruciating, that the songs had a reassuring therapeutic quality that tempered the personal experience of being mugged and beaten up in 2001 or that simply, still, to me, Kid A is Radiohead’s best album.

Significantly the reaction to this release was polarized. Factions developed that either loved or hated it. People were really, ridiculously upset and that always helps one cling to something as your own, in the adolescent sense, when the lumpen misshapen hordes don’t understand something that you love. For me, these dissenting groups brought to attention the social divisions of a particular culture, especially in the UK where rampant tribalism, barely concealed class conflicts and vicious judgemental colloquialisms are taken as normative modes of expression, and the divide in opinion dangerously teetered on a form of a culture war between those that declared their capacity to understand the textures of the album and those that just wanted to rock. The macro of this divide in opinion still exists in the micro of the Radiohead audience today. There are the Elois that smile with smug appreciation of what they consider to be the more demanding songs in the band’s catalogue and the Morlocks that bellow for the catharsis of something from The Bends. I’m naturally reticent to caricature myself either way. I’m probably a hideous hybrid of both creatures, half Morlock, half Eloi, bound together by the ten tracks released at the turn of the century.

In any case, the leap between OK Computer and Kid A wasn’t such a huge one, not if you were paying attention, and a lot of people were paying attention back then. The OK Computer B sides and the Meeting People is Easy film all hinted at what was to come, it’s just that the gap between what some expected and what happened on that CD had more to do what kind of band they thought Radiohead were, which actually had nothing to do with the band at all. For me, Kid A doesn’t contain the shock of the new but it exists as the logical extension of what came before, while still at the same time working as an exciting distillation of all that I thought the band were capable of, and herein lies the contradictory shock element, that they did it, the it being, they made a perfect album.

I’m not going to go into a laborious and unnecessary track-by-track analysis here or dissect the contemporary existential anxieties expressed in its form (2) but instead mention that not many artists live up to their full potential, and I know any interpretation of the word "potential" is tied to personal opinion, taste, and tedious psychoanalytic baggage. But a gap often exists between what you want from your artists and what you get (3) and maybe the final reason Kid A works as my favourite album is because for 48 minutes in the year 2000 that gap closed, fully, unmistakably, thrillingly and perfectly for good.

Notes

1. No, I don’t skip Treefingers.

2. The internet is drowning in them.

3. Naturally, some would say Kid A is the ideal encapsulation of this hypothesis.